I recently published an article on business leaders who are addressing climate adaptation with the help of an “agnostic adaptation” approach. I’ve gotten a lot of questions about what that means and if it’s appropriate: is agnostic adaptation a breakthrough to common ground, or the devil incarnate? Speaking solely for myself (and not the businesses involved or sources quoted here), here is my take. I’m very interested in yours.

Adaptation to physical climate change is an urgent necessity for business. While some companies are taking steps to truly adapt to what is already happening, far too many aren’t facing this new reality yet.

I’m working to help businesses that want to get moving on adaptation now. [For details, see “Facing the Future” on LinkedIn]. That’s a strategic and ethical imperative. The longer businesses wait, the more costs they incur and the fewer options they have. And the longer they wait, the more hasty and severe impacts on employees and communities are likely to be.

Personally, I think adaptation can also be the bridge to serious climate change mitigation, not a barrier or distraction. Once companies realize that climate adaptation is a matter of “here and now” and theirmoney, not “if and when” and somebody else’s money, views on fighting climate change may start to shift. But that’s a legitimate debate.

Why adaptation, why now?

Almost a year ago, I wrote: “It’s time to face climate change with acceptance. Not acquiescence, not resignation. But acceptance that we are where we are, it’s regrettable and scary, and we have to deal with it. Now and for the rest of our lives.”

That acceptance helped me recognize that physical climate changes are already affecting businesses around the world through increased frequency, intensity and duration of storms; flooding; drought; fires and extreme temperatures. Every aspect of business can be affected by these climate changes, including day-to-day operations and continuity, process safety, labor force, supply chain vulnerability, market access, capital expenditure, and even merger and acquisition activity.

Business has to adapt to that reality.

What is “agnostic adaptation”?

When I started working on adaption, I quickly encountered serious political “noise”. Some climate believers and activists saw adaptation as at best minimizing the dangers, and at worst sleeping with the enemy – as if I were suggesting that adaptation was sufficient, and not just necessary. At the same time, some climate deniers/skeptics saw adaptation as a “climate change activism” wolf in sheep’s clothing, a way to trick them into conceding the role of man-made climate change.

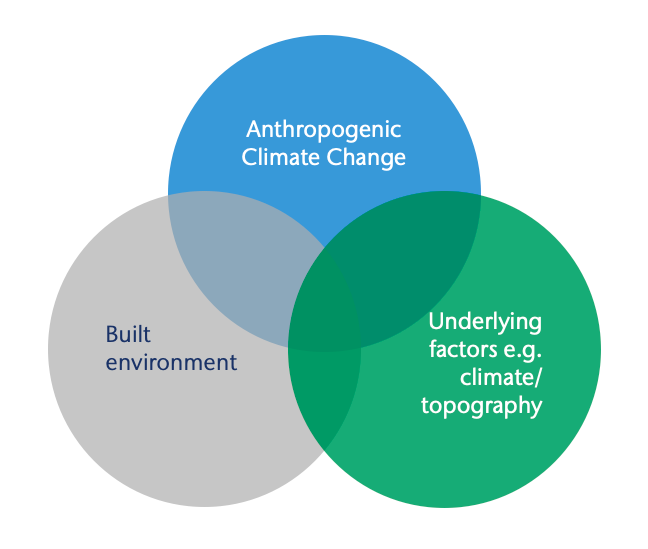

In discussions with business leaders all across the climate spectrum, I realized that there is still deep disagreement and discomfort in some parts of the business community around the causality behind changing weather and impacts, including:

- Is climate change a cause or a “magnifier” of other factors?

- Is built environment a cause or magnifier?

- Is climate change 10% of the cause or 70%?

Once in constructive discussion of adaptation, though, there was much less disagreement about the stressors (temperature and water) and their physical impacts. I realized that agreement on causality is not necessary for progress on adapting to impacts. By keeping the conversations agnostic as to causality, I was able to create “common ground” which could include any business.

I had stumbled into what Pace University Environmental Law Professor Katrina Fischer Kuh called “agnostic adaptation”. In 2016 she wrote:

“Agnostic adaptation means adaptation without the ‘why’—the divorce of adaptation from knowledge or acceptance of anthropogenic climate change. Adaptation is agnostic when one prepares for or responds to an actual or projected climate change-induced impact (e.g., a farmer plants a drought-resistant crop) without acknowledging that the adaptation is probabilistically or in fact necessary because of anthropogenic climate change (i.e., that drought conditions are caused or exacerbated by humans’ emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases).” In Contemporary Issues in Climate Change Law and Policy: Essays Inspired by the IPCC(Environmental Law Institute) by Robin Craig, Stephen Miller, 2016.

Is “agnostic adaptation” a break-through or a sell-out?

So is “agnostic adaptation” a break-through to create real progress, or a sell-out? Is it an enabler in the sense of something helpful, or in the drug-and-alcohol sense of encouraging and justifying negative, self-destructive behavior?

It’s a tough question. Liz Koslov, Assistant Professor of Urban Planning and Environment and Sustainability at UCLA, did a brilliant study of post-Hurricane Sandy adaptation in New York City. She found that agnostic adaptation worked – for some: “Agnostic adaptation minimized conflict, made for more tractable claims, and maintained relations of power but in so doing offered protection to only a select few.”

Another keen observer of urban development and inequity, Oksana Mironova, posed some tough questions including: “Will the adaptation strategies the businesses pursue make the impacts of climate change and other types of inequities (both inside and outside the business) worse? Is there a way to make sure that the businesses don’t just focus on extracting value from a rapidly deteriorating situation, but also carry some of the responsibility over mitigation (which may mean changing the things the businesses invest in and produce)?”

Anne van Valkengoed (researching Environmental Psychology at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands) gave me a blunt assessment of how I am applying agnostic adaptation to business:

On the one hand, I can see that this can have advantages, such as avoiding the political implications of climate change and getting bogged down in that debate. However, I also feel that it has disadvantages in the sense that it disconnects adaptation from what should be a unified and coherent response to climate change, that exists of both mitigation and adaptation strategies. … I feel that agnostic adaptation is not a viable long-term strategy, as you are essentially deceiving yourself about a truth that I think most people already know. Moreover, I think that we cannot respond sincerely and convincingly to a threat if we do not acknowledge exactly what we are facing.

In practice, avoiding the causality debate clearly helped my Business Adaptation Workshop stay on topic. Even participants from companies which have taken strong positions on climate change and mitigation still observed that it was easier to focus on adaptation by avoiding the causality debate.

And for at least some companies, looking at their adaptation strategy spontaneously raised the question of how this compared to their mitigation strategy – if they had one.

So far, I think I’m being intellectually honest by viewing adaptation as necessary but not sufficient – but not requiring others to swear loyalty to that view. But that’s just what I think so far.

What do you think?

[Opinions in this blog are solely those of Scott Nadler. They do not necessarily represent views of Nadler Strategy’s clients or partners, or those cited in the post. To share this blog, see additional posts on Scott’s blog or subscribe please go to nadlerstrategy.com.]